What Settles in the Light responds to a commission from the British Journal of Photography and the Bodleian Libraries to create portraits that enter the Libraries' permanent collection—a visual chronicle spanning 988 to 2009. The commission's theme, "Catalysts," sought to address diversity gaps in both sitters and artists while capturing pivotal forces driving significant, long-term global impact.

The project brings together Vice-Chancellor's Award recipients and researchers whose stories reveal what catalysis means. Professor Nandini Das excavates trans-cultural histories challenging empire narratives whilst navigating her own multiple heritages. Professor Steve Strand, who nearly failed his A-levels, builds evidence-based frameworks addressing the educational inequalities he once faced. Alexis McGivern and Clarissa Salmon have trained 4,500 young climate activists across 177 countries. Dr Anne Makena and Professor Kevin Marsh created the Africa Oxford Initiative from complementary perspectives – she, an African doctoral student who'd navigated Oxford's barriers, he a researcher returning after 25 years in Kenya. The “We Are Our History” team – Antony Brewerton, Helen Worrell, Lanisha Butterfield, Abigail Hopkin, and Peter Brathwaite – led the Bodleian's institutional reckoning with race and colonial legacies, each bringing different expertise to collective transformation. Dr Samina Khan, three years old when she arrived from Pakistan to Leicester, now transforms how Oxford engages communities that are told the university "isn't for them." And finally, Professor Sir Peter Horby, whose RECOVERY trial redefined the pandemic response through a 15-minute conversation and 9 days of relentless work.

At its core, this project uses oral histories and photography to capture catalysts through their own voices – inviting each person to tell their story of becoming. It traces the journey from who they were to who they are now, creating a moment to reflect on the work that defines them. These conversations form the foundation for visual triptychs exploring three distinct moments: the details of their work, the spaces where we see its impact, and portraits of the people who initiated change. This approach mirrors how we actually encounter both research and lives: first through effects, then through contexts, and finally through the individuals themselves.

Alexis McGivern & Clarissa Salmon

Global Youth Climate Training, Oxford Net Zero

Positioned in the Delegates' Room—a space where historic decisions have reverberated for centuries—Alexis and Clarissa embody what they call being "radical insiders": working within Oxford's systems whilst remaining conscious of the institutional legacies they seek to dismantle.

Through the Global Youth Climate Training, they've moved beyond symbolic inclusion. Over 5,400 young activists from climate-vulnerable regions have accessed technical expertise that fundamentally shifts their capacity to participate in UN climate negotiations. Alexis recalls the moment she watched applications flood in—12, then 200, then 3,000, eventually 10,000 across two weeks from 177 countries. That crystallised their understanding of catalysts: small actions initiating something far larger than the effort itself.

Their commitment is uncompromising: young people need knowledge, genuine access, and to be paid for their labour. They refuse the extractive model. Standing here, they carry the clarity of those who understand both power and purpose.

Professor Steve Strand

Professor of Education, University of Oxford

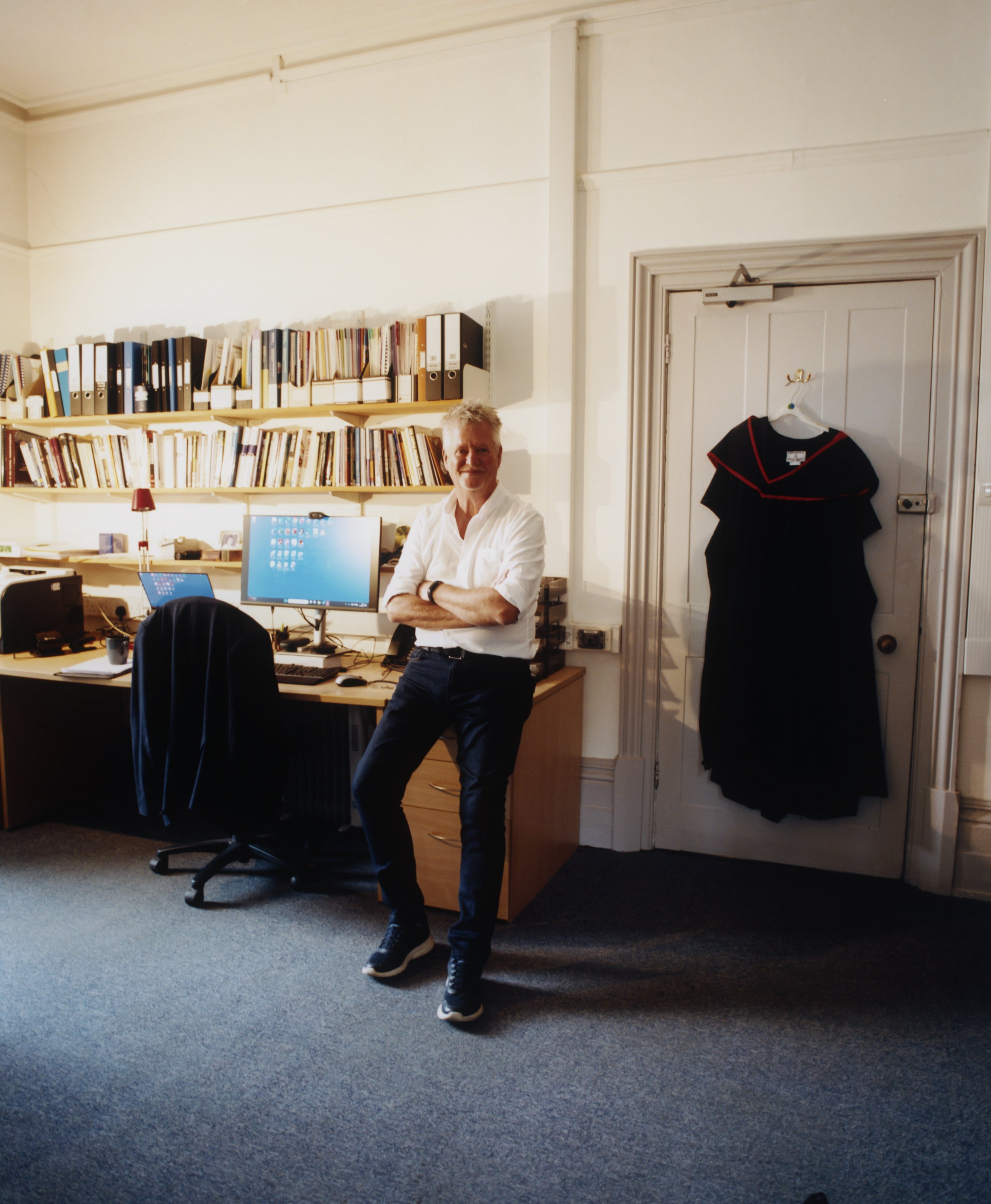

Professor Steve Strand has spent four decades asking uncomfortable questions about who succeeds in British education, and why. His office at Oxford, where decades of research accumulates, has been the site of work influencing House of Commons inquiries and challenging governmental assumptions about educational inequality. "If research hasn't got direct implications for practice or policy, then what's the point?" It's not an abstract question for someone who nearly failed his A-levels before discovering academic purpose at Plymouth Polytechnic.

Starting with a project identifying five-year-olds at risk of reading failure, he's built a career examining how ethnicity, class, and language intersect with educational outcomes. His work demonstrates truths policymakers resist: educational failures aren't school problems but social ones. No amount of academy restructuring compensates for unemployment, inadequate housing, and fragmented community support. His research provides evidence making these realities harder to dismiss, using Oxford's institutional weight to ensure marginalised students' educational journeys are properly contextualised.

Photographed in his workspace, doctoral gown hanging behind him like scholars in centuries of Bodleian portraits, he represents patient accumulation – decades of findings that shift policy conversations incrementally but meaningfully. Meeting him, I felt both grateful such research exists and saddened by how few others pursue it. He's the kind of catalyst whose work creates foundations others might not even recognise they're building upon.

Dr Anne Makena & Professor Kevin Marsh

Africa Oxford Initiative

"How I got into this position is fluke," Anne Makena laughs, recalling a 2015 conference where she met Kevin Marsh. But nothing about the Africa Oxford Initiative they built together feels accidental. Anne, finishing her DPhil and knowing Oxford's barriers firsthand, and Kevin, returning after 25 years leading research in Kenya – they approached the same problem from opposite directions and arrived at identical conclusions. Oxford's famously devolved structure meant African collaborations were happening everywhere, but no one could see what others were doing.

What they created wasn't a programme marching from Oxford declaring what Africa needs. They offered what Anne calls "a floor and a roof" – infrastructure where existing work could become visible, where scattered energies could synergise. Even the naming was deliberate: "AfOx" not "OxAfrica," acknowledging that Africa is, as Kevin notes with characteristic understatement, somewhat bigger than Oxford. Their fellowship programme grew from three places to 16 to 24 as colleges witnessed the impact. Now India Oxford, Caribbean Oxford, and Pakistan Oxford initiatives emerge from the same ethos.

Photographing them together in the Clarendon Building's warm light, I watched how they finish each other's sentences, that easy partnership built over eight years of transformation. What struck me wasn't just their professional achievement but their obvious care for one another, their shared commitment to rebalancing power in global knowledge ecosystems. Catalysts make change replicable.

Dr Samina Khan

Director of Undergraduate Admissions and Outreach, University of Oxford

"I'm actually an organic chemist, so I have a definition for being a catalyst," Dr Samina Khan tells me, before offering something far more personal than molecular interactions. She understands catalysts as spaces bringing different ways of thinking together, helping everyone reach where they want to go faster. It's an apt description for her work directing Oxford's Undergraduate Admissions and Outreach.

Her own journey informs everything. Three years old, arriving from Pakistan to Leicester's Highfields, living with extended family in close quarters, her father insisting education remains your foundation no matter what. Teaching in North London and Birmingham state schools, she gravitated toward students needing institutional support their homes couldn't always provide. At Oxford since 2012, she's transformed how the university engages communities – not waiting for them to come to Oxford's doorstep but going to Bradford, Oldham, Birmingham, Cornwall. Her team develops evidence-based tools helping admissions tutors understand different educational routes: free school meals, comprehensive schools, accents some wrongly assume won't be understood.

Her dream is technical – Oxford, reflecting UK students achieving three A's proportionally. But what makes her heart sing? That medical student approaching her in Bradford: "I saw that South Asian woman and thought, so can I." One Saturday morning, one profound ripple. Her only request to those reaching Oxford: don't close the door behind you.

Professor Nandini Das

Professor of Early Modern Literature and Culture, University of Oxford

We could have talked for hours. Professor Nandini Das moves between worlds with such fluidity – from sixteenth-century Portuguese-held Goa to contemporary Oxford, from technical discussions about Renaissance literature to intimate reflections on code-switching and belonging. Born in West Bengal where English literature became a colonial tool, she now excavates stories of trans-culturality: "It's not simply two cultures meeting each other," she explains. "It's about people navigating two or three different things at the same time" – creating something neither one heritage nor the other but entirely new. Her scholarship on travel, migration, and cross-cultural encounters feels urgent precisely because, as she observes, history keeps repeating itself – even Tudor complaints about foreigners raising rents in London echo today.

Photographing her in her office and tutor room at Exeter College, I was thinking about the historical portraits already in the collection – those contemplative poses, hand to face, figures lost in thought across centuries. That gesture connects her to the intellectual tradition she both inhabits and interrogates. Her British Academy Prize-winning Courting India traces how England's relationship with Mughal India shaped empire's origins, revealing patterns we're still navigating. Her forthcoming book examines how sixteenth-century England was shaped by constant mobility – sailors, merchants, and displaced people crisscrossing continents.

What struck me most was how she embodies her research: moving between languages and contexts, understanding that knowledge itself travels, transforms, refuses to stay still. A catalyst doesn't just spark change – sometimes it reveals what's always been in motion.

Professor Sir Peter Horby

Director, Pandemic Sciences Institute, University of Oxford

Nine days. That's how long it took from a fifteen-minute conversation to enrolling the first patient in what became the RECOVERY trial – the largest randomised clinical trial in history. On 10th March 2020, Professor Sir Peter Horby sat in Chris Whitty's office and outlined his plan: fast, simple, big. Three principles born from two decades preparing for a pandemic he hoped would never come. Whitty listened for ten minutes. "Okay, do it."

What followed redefined what's possible in clinical research. At peak, RECOVERY enrolled over 500 patients daily across 190 NHS hospitals, testing 16 treatments with thousands of clinicians randomising patients at point of care. Dexamethasone worked; hydroxychloroquine didn't. Clear answers in months, not years. The FDA later reviewed 2,000 COVID trials and concluded 95% were "designed to fail" – too small, poorly randomised, unable to provide regulatory data. RECOVERY set a new benchmark.

Speaking about being a catalyst, Peter's humility surfaces immediately: "Twenty years being a pandemic diseases researcher, and if I'd screwed up during the only pandemic of my life, it would have been a bit embarrassing." But he's changed something fundamental. Now, meeting colleagues in Bangladesh or Democratic Republic of Congo about Ebola outbreaks, "the mindset is different. Okay, we need to do it, and we can do it." Research isn't a luxury during health crises – it's how you provide good care.

What he finds "inspiring and depressing in equal parts" is knowing we could do this for dementia, for everything. But memory fades quickly. Systems revert to risk-averse habits. Meeting Peter, I felt the weight he carries – not just what he achieved, but his awareness of what remains possible if we remember.

We Are Our History

Helen Worrell, Lanisha Butterfield, Antony Brewerton, Abigail Hopkin, and Peter Brathwaite

"History is not the past, it is the present. We carry our history with us. We are our history." The James Baldwin quote that named this project captures what five people achieved together over two years at the Bodleian Libraries. Ant Brewerton, Helen Worrell, Manisha Butterfield, A Hopkin, and Peter Brathwaite – each brought different expertise to examining the institution through the lens of race and empire's legacies, making recommendations across collections, audiences, and staffing.

What made We Are Our History catalytic wasn't just its scope but its refusal of compartmentalisation. Eight workstreams meant everyone could see how the work connected to what they did daily – not something happening "over there" but embedded throughout the organisation. They commissioned challenging artwork (a portaloo with burnt union flag), supported security staff through difficult conversations, built audiences who'd never visited the Bodleian before, curated displays revealing untold stories in the archives. A Hopkin describes catalysts as "the tipping point where you move from intent to action" – years of discussion becoming concrete commitment.

Photographing all five together outside presented technical challenges, but it felt essential. This wasn't individual achievement but genuine collaboration – community, care, taking turns speaking about their contributions. Ant, trained in shushing people, remembered Peter's event ending in song. That moment captures what they built: a Bodleian transformed not through policy alone but through people brave enough to do the work holistically, together.

Acknowledgments

This body of work and exhibition would not have been possible without the generosity, trust, and openness of Oxford University's research community. My deepest gratitude goes to all who shared their stories, insights, and time with me.

Special thanks to the sitters who allowed me to photograph them and record their stories: Professor Nandini Das, Alexis McGivern and Clarissa Salmon, Dr Samina Khan, Professor Peter Horby, Professor Steve Strand, Dr Anne Makena and Professor Kevin Marsh, and the We Are Our History team. Your candour and commitment to this project form the backbone of this work.

I am enormously grateful to the Bodleian Libraries for their vision in commissioning this work, and to the British Journal of Photography for their partnership in bringing contemporary voices into the Libraries' millennial collection. Particular appreciation goes to Lanisha Butterfield at the Bodleian Libraries and to Sinead and Zoe at the British Journal of Photography, whose support and dedication to this project sustained it from conception to completion.

I am appreciative of Aniella Weinberger for her invaluable assistance throughout this commission.

Thank you to all who believed in this project's potential to contribute meaningfully to the Libraries' historic collection whilst addressing its contemporary gaps in representation.